Publishing models that actually work

Most organisations treat publishing as a binary choice: control everything centrally, or let teams do their own thing. Neither extreme really serves their users well.

The organisations I've seen succeed take a more pragmatic approach. They're intentional about what needs consistency and what benefits from local ownership. The result isn't a compromise; it's a model that actually fits how their users behave and how their teams work.

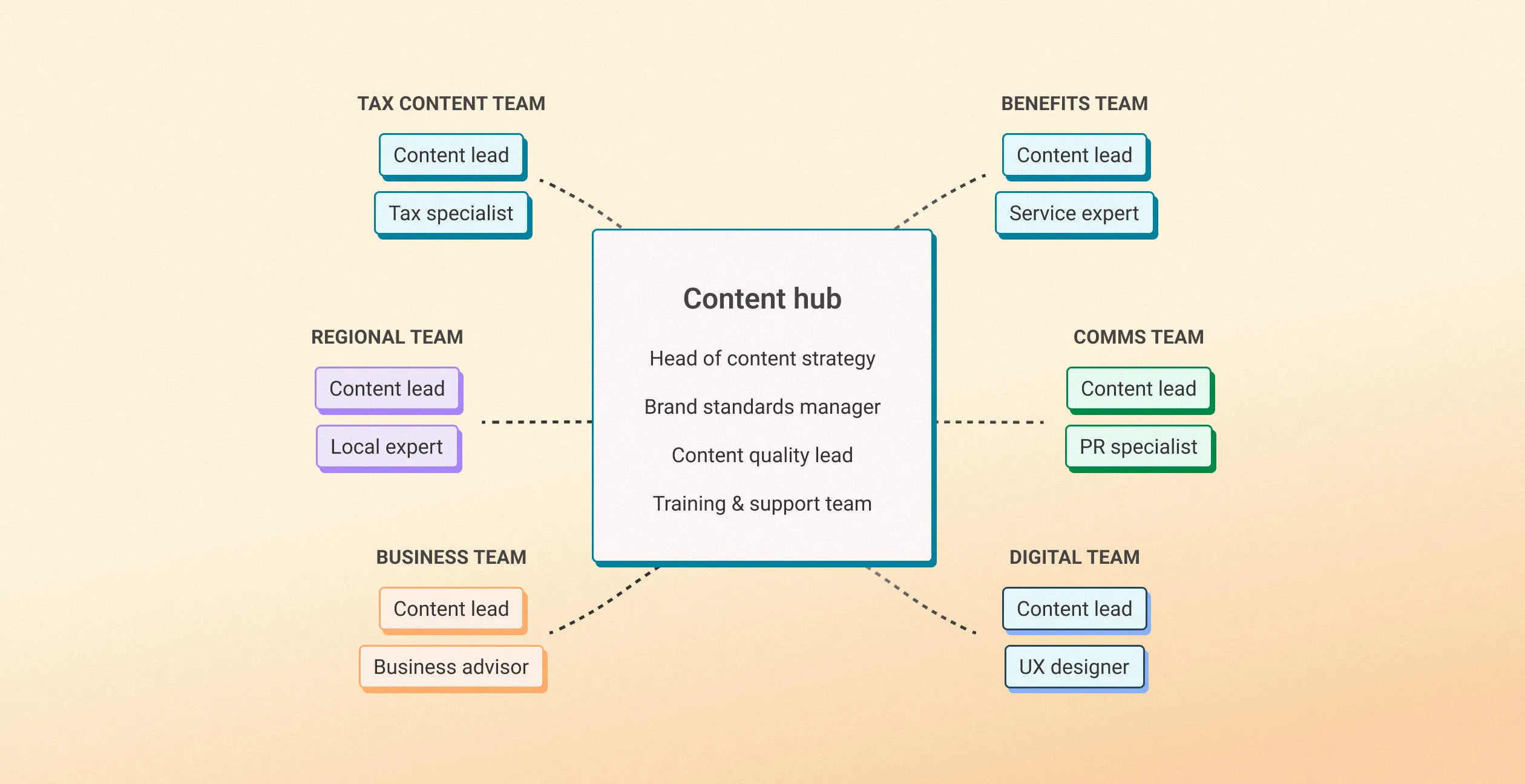

Hub and spoke: standards with empowerment

The hub and spoke model offers a middle ground that works particularly well for large, complex organisations. A central 'hub' team sets standards, provides training and offers support. Then 'spoke' teams in each department create content independently within that framework.

This works well in local authorities where content spans multiple service areas. Someone looking for help with housing costs might also need information about council tax support, free school meals or social care. Users shouldn't encounter completely different experiences as they move between services. But the people who understand housing policy aren't the same people who understand council tax, so you need local expertise operating within shared standards.

In universities, the same logic applies. Prospective students move between course information, accommodation, fees and student support. Each area has specialist knowledge, but the user journey needs coherence. A hub-and-spoke model lets faculty teams own their content while the central digital or communications team maintains consistency where it matters – navigation, core application journeys, institutional messaging.

What makes this a successful publishing model is clear role division. The hub doesn't create content; it enables content creation. It provides templates, guidelines, training, and quality assurance. The spokes don't work in isolation; they have support and standards to lean on. Neither is waiting on the other; both have clear responsibilities.

The hub team typically focuses on content strategy, brand standards, quality assurance, and training. Each spoke has someone responsible for content who works closely with subject matter experts – whether that's a service manager in a council or an academic programme lead in a university.

I've seen this model transform organisations that were struggling with both centralised bottlenecks and decentralised chaos. It gives departments the autonomy they need while maintaining the consistency users deserve.

Hybrid models with intentional boundaries

Beyond hub and spoke, successful hybrid models establish what genuinely matters centrally and free up everything else for local decision-making. The key is being intentional about what needs consistency and what benefits from variation.

Users care about some things being consistent like navigation, core processes, the basics of how your organisation communicates. They care about other things being locally relevant like examples that reflect their situation, content that acknowledges regional differences and specialist information that goes deep rather than staying general.

Here's what I've found works best:

Centralise:

- Brand standards and visual identity

- Core user journeys and navigation

- Accessibility and inclusion standards (particularly important given public sector duties)

- Legal and regulatory compliance

- High-stakes content such as emergency communications, policy announcements and anything with reputational risk or regulatory implications

Distribute:

- Routine service and content updates

- Specialist content that requires deep expertise

- Local examples and case studies

- Departmental, faculty, or service area news

- Time-sensitive announcements where speed matters

- Content for specific audience segments that local teams understand best

In a council, this might mean central control over the main service pages and transactional journeys, but local ownership of community news, events, and specialist guidance. The "apply for a parking permit" journey stays consistent; the "what's on in your area" content reflects local knowledge.

In a university, it might mean institutional brand standards and a consistent prospectus experience, with flexibility for research groups to communicate with their academic communities and professional services to own their specialist content. The student application journey is centrally managed; departmental research pages are locally owned within brand guidelines.

Why the extremes can fail

Understanding why pure models struggle helps explain why these alternatives work better.

The problems with centralised control

Centralised publishing gets a bad reputation for being rigid and bureaucratic. Sometimes that reputation is deserved.

Central teams become bottlenecks when they don't have the knowledge or capacity to make quick decisions. I've seen critical user guidance delayed for weeks while it went through central review. This wasn’t because it was wrong, but because the reviewers didn't understand the context well enough to approve it confidently

In a university, central teams rarely understand the nuances of individual research areas, professional accreditation requirements, or the specific needs of international student cohorts. In a council, they can't know every service, from pest control to planning applications to social care, as deeply as the people delivering those services every day.

Specialist content often suffers under centralised control. Technical documentation written by content generalists lacks the expert precision users need. Service guidance written by people who've never handled a query lacks the practical detail that helps residents.

The problems with decentralised publishing

Decentralised publishing creates problems users actually feel. Different teams create different experiences. Users encounter:

- Contradictory information about the same topic

- Content that’s inconsistent in quality and clarity

- Navigation that reflects organisational charts, not user needs

- Duplicated content that goes out of sync

- Inconsistent tone that undermines institutional credibility

For a council, this erodes trust in services people depend on. If residents can't rely on your content to be accurate or consistent, they phone instead – which costs more and helps no one. For a university, inconsistency undermines the professionalism that justifies the fees and shapes reputation.

The cost isn't just user confusion. It's content maintenance challenges, brand erosion, and the gradual loss of confidence in your content as a reliable source.

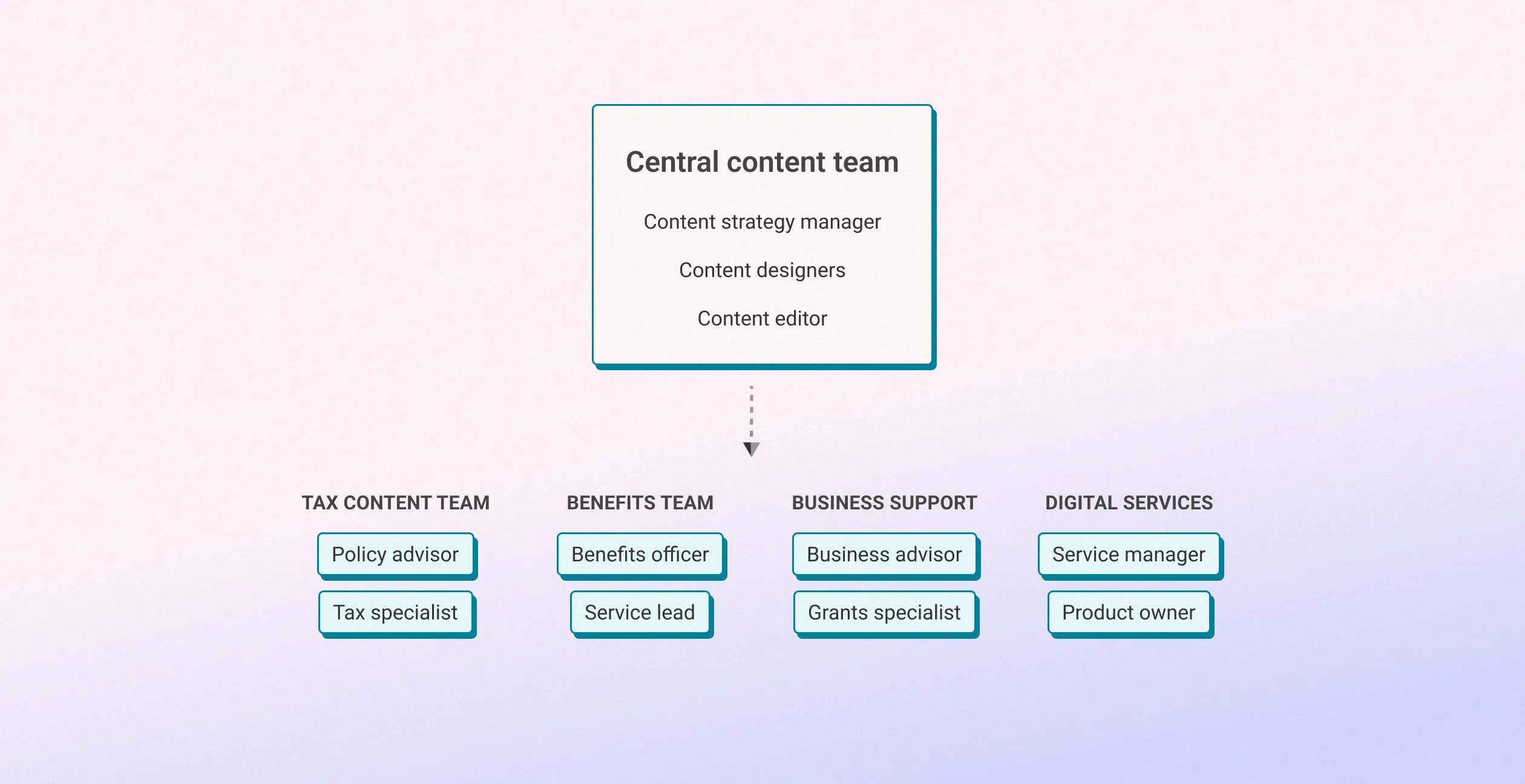

When centralised control does make sense

Centralised publishing isn't always wrong. It works when:

- Content quality varies dramatically across teams and users are suffering as a result

- Subject matter experts lack content skills and can't develop them quickly

- Legal, regulatory, or accessibility requirements are complex and high-risk

- User journeys cross departmental boundaries and need to feel seamless

- Organisational reputation depends on content quality and consistency

An example of this in practice would be where a central content team transforms incomprehensible policy documents into clear, actionable guidance. The service experts provide the accuracy; the content professionals provide the usability.

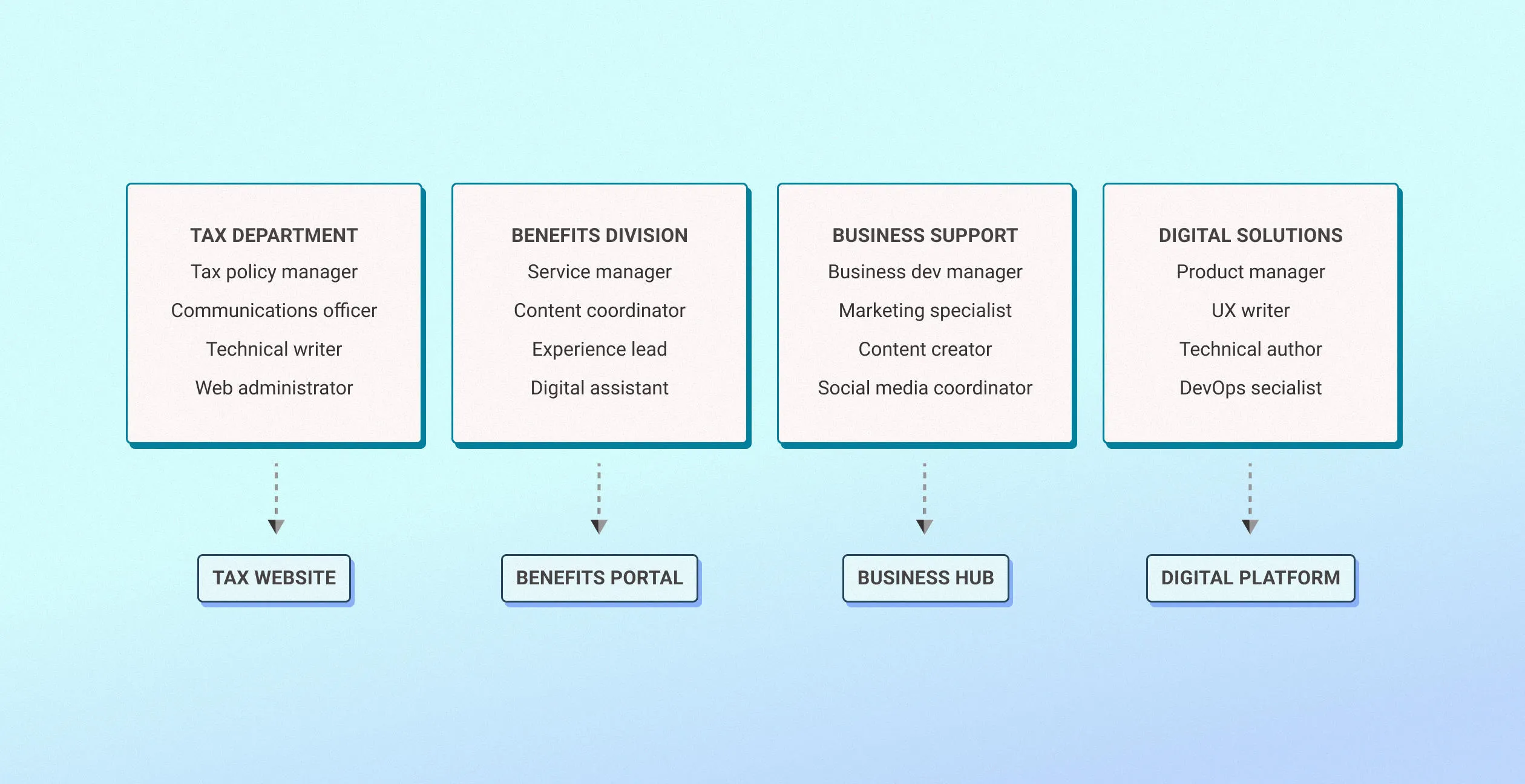

When decentralised publishing does make sense

Local teams often understand their users better than central teams. A service team knows which questions residents actually ask. A faculty team knows what prospective students worry about. A specialist department understands nuances that matter to their specific audience.

Decentralised publishing works when:

- Local teams have strong content skills or can develop them

- User needs vary significantly by service area, faculty, or audience segment

- Speed matters more than perfect consistency

- Content requires deep specialist knowledge that central teams can't replicate

- Teams are distinct enough that one-size-fits-all doesn't fit anyone

The solution isn't to choose a side. It's to be deliberate about which content needs which approach.

Making the transition

Changing publishing models is a cultural and operational change that affects everyone who creates, reviews, or maintains content.

Moving from fragmented publishing toward more structure

If decentralised chaos is your problem:

- Start with content that matters most to users, not content that's easiest to fix

- Audit existing content to understand where quality and consistency are actually failing

- Find teams already producing good work and learn from them – don't assume the centre knows best

- Create standards that solve real problems people recognise, not theoretical ones

- Implement gradually, proving value at each step rather than mandating change upfront

Loosening central control

If centralised bottlenecks are your problem:

- Identify where delays are hurting users or frustrating teams

- Find teams ready and able to take on more responsibility – not everyone will be

- Be clear about what stays centralised and why

- Provide training and support so teams can succeed, not just permission to publish

- Monitor quality and user outcomes closely in the early stages

- Be prepared to adjust boundaries as you learn what works

Bringing people with you

Publishing model changes affect everyone involved in content. Successful transitions require:

- Clear communication about why change is needed – show people the problems the current model creates for users, not just the benefits of the new approach

- Training that builds confidence, not just instructions to follow

- Support during the transition, because people will make mistakes and need help

- Feedback loops that let you adjust as you learn what's working

For teams worried about losing autonomy, explain what they'll gain – speed, relevance, ownership – and what safeguards are in place. For central teams worried about losing relevance, reframe their role from gatekeepers to enablers. Show how they can add more value by supporting and upskilling than by controlling and approving.

Choosing based on user outcomes

The right publishing model isn't the one that makes internal processes smoother or keeps any particular team happy. It's the one that helps users find what they need, complete their tasks and trust your content.

For many organisations, that means some version of hub and spoke or a thoughtful hybrid – central standards where consistency genuinely helps users, local ownership where specialist knowledge and speed matter more. The balance will be different for every organisation, but the principle is the same: be intentional about the boundaries.

Measure success by user outcomes. If residents can't find the right service, if students can't get clear answers about their course, if people are phoning because they don't trust the website then the publishing model is failing, however tidy it looks from the inside.

Good publishing models are invisible to users and empowering to the people who create content. They make it easier to publish things that help and harder to publish things that don't.